Down in the Dead Hotel

Joseph Mitchell migrated to New York from the South to become a political journalist. That idea flew somewhere else. He haunted the fish market and hotels, and wrote about such places and their people for a great magazine. Then he stopped.

He still wandered the city, haunted his places and wrote, but never handed in another story for publication. He still went to his office at the magazine on work days, and the magazine paid him for it, for decades.

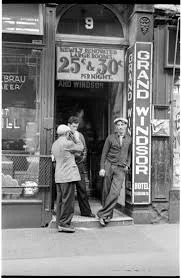

The city he’d come to as a young man was on its way out. He roved the shadows of places that’d been torn down, gathered remnants from defunct hotels: doorknobs, towels, silver-plated utensils. He filled his apartment with them.

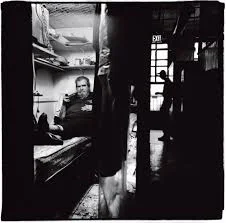

A hotel lobby is a public place. Once it was usual for city dwellers to live in hotels. The lobby was everyone’s living room.

Mitchell attended life as it went on in the living rooms of Bowery flophouses. He wasn’t there to gawk. He drank and raved, did what flophouse denizens do.

Then he wrote about what happened.

Until he felt he couldn’t do it any more. The city he wrote about had become a dream. He was a ghost in an office, but it was the kind of office that those who want to do what he did dream about.

Those low hotels are gone. Mitchell’s office is gone too, or has become something other than what it once was. The streets and places have the same names, but any other similarity is purely historical, and coincidental.

A young couple recently checked into the Kranepool as “Mr & Mrs Gould”. They left behind a copy of Joseph Mitchell’s bestseller anthology, and a partial manuscript. The book went onto a shelf in the lobby, the loose pages into the shredder. Except for this scrap, which the Night Porter found tacked to the bulletin board in the Management Office, where he wasn’t officially supposed to be.

"On the bus ride down to the Big City, we talked about the Hare Krishnas, or some hippie commune where we might stay. Bat Norton had scrawled a few hotel names on an envelope, cheap places he said we could try. They were all on the Bowery, the last resort of bums. The flophouses smelled of second-hand alcohol and piss.

Home was an increasingly cage-like trailer stuffed with empty vodka bottles and dirty clothes. Pop was unemployed and depressed.

We looked around a while, then stopped on a corner in the light of a movie marquee. We didn’t know what to do. It was cold and getting dark. A woman shrieked in one of the crummy buildings, and the sound started a bunch of men laughing. Whatever hung in the air between me and Big Babs set like concrete.

The rummie at the desk of the Kranepool Arms (n.b. no relation) asked if we were married. I was about to say oh yes of course sir, but Big Babs said, "We're not married. We just want to be together tonight, if that's all right with you."

The guy shrugged, and forked over a key on a wood fob that looked like it’d unlock the toilet at the rear of a gas station.

An outhouse would’ve been an improvement on where Big Babs and I spent our high school honeymoon night, but there was a bunk and there was us and there was no other world."

Giù nell’albergo morto

Joseph Mitchell migrò a New York dal sud per fare il giornalista di politica. Cambiò idea. Bazzicò il mercato ittico e gli alberghi, scrisse di quei posti e del loro popolo per un ottimo settimanale. Poi smise.

Continuò a girovagare per la città, frequentò i suoi luoghi prediletti e scrisse, ma non passò più pezzi alla redazione. Si presentava in ufficio, lavorava, ma non volle pubblicare più nulla. La rivista continuò comunque a pagarlo.

La città dov’era arrivato da giovane stava scomparendo. Joe rovistò tra le sue ombre e macerie. Raccolse rimasugli di alberghi defunti. Ne riempì il suo appartamento.

Una hall d’albergo è un luogo pubblico. Una volta era normale che la gente di città vivesse in hotel. La hall era il salotto di tutti.

Mitchell presenziava alla vita come veniva vissuta nei salotti dei bassifondi. Non era lì solo per sbirciare. Beveva, ciarlava, faceva ciò che facevano i residenti di quei posti. Scriveva di questo.

Finché sentì di non esserne più capace. La città di cui aveva scritto era diventato un ricordo. Lui era un fantasma in un ufficio, anche se era il tipo di ufficio di cui sognano quelli che vorrebbero fare come aveva fatto lui. Quei truci alberghi non esistono più. Anche l’ufficio di Joe è sparito, oppure è diventato qualcos’altro. Le strade e i luoghi hanno gli stessi nomi, ma ogni altra somiglianza è solo storica, e puramente casuale.

Di recente, una giovane coppia venne al Kranepool e si registrò come “Sig. e Sig.ra Gould”. Lasciarono nella stanza una copia dell'antologia bestseller di Joseph Mitchell, e alcune pagine manoscritte. Il libro finì sullo scaffale per libri lasciati dai graditi ospiti, i fogli nel distruggidocumenti. A parte questo frammento, che il portiere di notte trovò affisso sulla tabella nell’Ufficio Gestione, dove ufficialmente non avrebbe dovuto essere.

“Sulla corriera diretta in città parlammo degli Hare Krishna e di comunità hippie dove forse potevamo stare. Bat Norton aveva scritto qualche nome d’albergo su una busta, posti che costavano poco. Erano tutti sul Bowery, il viale dei barboni. Quelle stamberghe puzzavano di alcol passivo e piscio.

Casa mia era una roulotte sempre più piena di bottiglie vuote e panni sporchi. Papà era disoccupato e depresso.

Venne buio, e faceva un grande freddo. Eravamo fuori, indecisi. Una donna strillò, e degli uomini si misero a ridacchiare. Quel che c’era per aria tra me e Big Babs si solidificò come cemento.

L’ubriacone dietro il banco al Kranepool Arms (n.d.r. nessun rapporto) chiese se eravamo sposati. Stavo per dire oh certo signore, ma Big Babs disse, “Non siamo sposati. Vogliamo solo stare insieme stanotte, se non ti dispiace.”

Il tiziò alzò le spalle, e ci mollò una chiave che sembrava quella del cesso di un distributore di benzina su un’autostrada sperduta.

Quel cesso sarebbe stato più bello della stanza dove io e Big Babs facemmo la luna di miele liceale, ma c’era una branda e c’eravamo noi e non esisteva un altro mondo.”